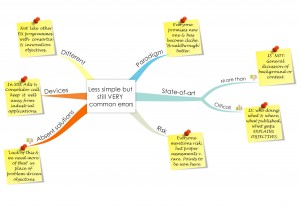

The next issue that I’d like to deal with as I move one step around the mind map of common but more complex problems is the most important that we have encountered so far and one of the most important of all i.e., writing the state-of-the-art description.

Presenting the state-of-the-art is right at the heart of a successful proposal and is poorly done very often and if the proposal gets off to a bad start on this key section it proves very difficult to get it back on track later – the information set out at this stage of the work is so critical to the argument, in fact, that it is the foundation of the whole edifice.

Too often the state-of-the-art is treated as a general discussion of the field and some of the issues in it currently, or not so currently in many cases. It too often remains at a very high level of generality and acts more like orientation than forceful argumentation. The writer might discuss the field and the sub-field without any particular argument being created and no fine detail being offered. The job is clearly often considered to be scene setting or general contextualisation or background information and far too much gap filling is left to the evaluator’s imagination. And on the basis of this the writer will likely progress to the presentation of the objectives which sit loosely inside of the framework of the general context.

On such a shaky foundation it is almost impossible to create clear and important objectives as there is simply not enough substance for the reader to understand why these objectives are the critical ones and why this project is more attractive than the dozens of others in the pile.

In brief, and this is a topic that we’ll return to in future posts, the state-of-the-art argument must be a detailed description of the very latest meticulously documented information about who is doing what, where they are working and what they are publishing. The aim of the section is to show mastery of the field, right-up-to-date knowledge of the research trajectories, debates and controversies and crucially the weakness in them: it is a critical turning point in creating the argument and establishing the researcher as a credible candidate. It is only from the shortcomings or blind spots of current research that the proposer will be able to generate their objectives – or at least this is the best, quickest and simplest way to create very robust and logical objectives which are the best kind by far.

So, I’d suggest that a really convincing proposal needs to be able to go down to the level of “and prof. X is doing this at this place and has published here while Dr. Z from this institution is doing this and that and has reached these conclusions as can be seen very clearly in this publication from…” etc. With this level of detail already your proposal will be standing head and shoulders above the (very large) crowd as very few people do this with the required level of commitment and succeed in creating a strong bedrock for the objectives. It also makes it very easy to read and to follow the unfolding logic which is vitally important, so for logic and rhetoric it has lots to recommend it.

The state-of-the-art discussion has a very clear and important job to do. The whole point of the discussion is to allow the researcher to reveal the project objectives which are the real beating heart of the work and the reason why the ERC will or won’t buy the project. The logic of the state-of-the-art presentation is always, when it is boiled down, the same thing. The job is to show that you are able to take a good general look at the work going on to orientate the reader, that you can then delve right down into the very fine detail of the key issues emerging from latest research and know who is doing that and that you can argue convincingly to show the weaknesses of what if being done.

So, the story is that “this is where we are, this is what is going on and who is doing it, it is pretty good in the circumstances and going well with lots of fascinating stuff coming to the surface, however, if we really want to get to the bottom of things and deliver the big benefits the field promises we are not going to be able to do it with these assumptions and by following these trajectories, so, therefore, the best way forward is…”

And the project objectives are then the detailed promises to deliver new and highly ambitious benefits by the end of the project to fill in these gaps. I can think of very few successful projects where this basic argument doesn’t apply. The simple logic is that the project objectives drop out of the weaknesses in the state-of-the-art, that the pressing concerns of the field will not be addressed nor its problems solved unless these highly innovative, challenging objectives are achieved.

Therefore, I’d argue that without a really good background in the state-of-the-art and the problems that it won’t solve it is difficult to put the objectives of the new project into a high enough relief for them to be convincing and to carry the weight of the rest of the project. Quite simply, the best way to get to really high impact objectives is to let them drop out of the gaps in the state-of-the-art.

The bigger and more well known the problems that you’ll promise to solve are the more attractive and higher impact the project appears to be. The downside to this is that commonly researchers think that it is attractive and a selling point to promise very major breakthroughs, or even paradigm shifts (see an earlier post for the problems with the use of the idea of the paradigm shift in ERC proposals) when mostly it isn’t. A too ambitious claim will go down just as badly as a proposal that is not promising enough in my experience.

The job of setting the right level of ambition is a fairly simple scoping task. One way of doing this is to look at the maximum budget and the work that can be done in the field for this – given that most people work from the maximum backwards rather than from real costs upwards as you would more likely to be doing in a private sector project where the case for resources is a much tougher one to make. With this in mind the size of the objectives to be reached can be sketched out given how much work will be possible in the time and budget. It is then a fairly straightforward task to select objectives in the gaps of the state-of-the-art that are the right size for the programme i.e., ones that promise significant sustainable benefits which can be achieved completely inside the project and which will open new horizons to future lines of research beyond the project’s life cycle.

Like all aspects of writing the proposal and planning the work it needs to be done ruthlessly to win within the rules we are playing by here – the best and most saleable objectives might not be the ones that are nearest to hand, or easy to do, or your pet topics or something well over the horizon. Good objectives need to be designed and manufactured for the particular job in hand and will need to be forced into the structure that we are presented with if they are to create the strongest likelihood of success. So look for ambitious but realistic and feasible, opening onto the future but plannable and predictable – we have to work out as logically as possible what the sweet spot is given the project size, the issues in the field, personal capacities and the impact that is going to be promised. In my experience of working with researchers there is always such a sweet spot to be located that makes the work pretty hard to resist, it is simply that most researchers don’t spend the time to find it. And all this begins with a clear setting out of the state-of-the-art, to return to the topic of this post.